In June, the United Nations called the situation a “growing humanitarian and safety crisis.” And there is still no solution in sight.

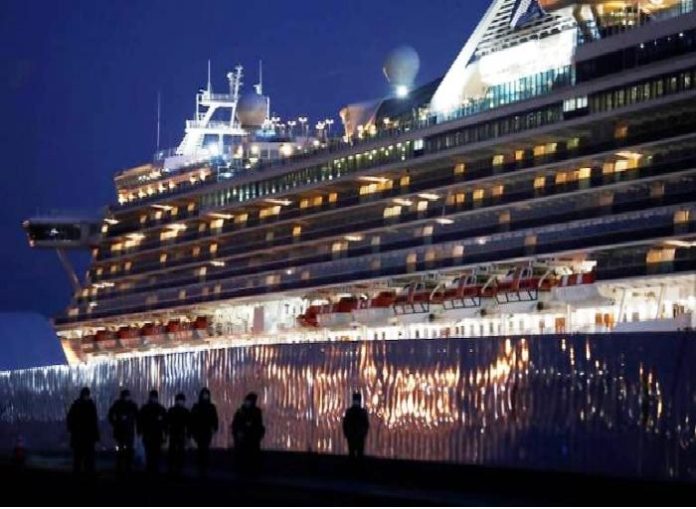

Last month, the International Transport Workers’ Federation, a seafarers’ union, estimated that 300,000 of the 1.2 million crew members at sea were essentially stranded on their ships, working past the expiration of their original contracts and fighting isolation, uncertainty and fatigue.

“This floating population, many of which have been at sea for over a year, are reaching the end of their tether,” Guy Platten, secretary-general of the International Chamber of Shipping, which represents shipowners, said Friday. “If governments do not act quickly and decisively to facilitate the transfer of crews and ease restrictions around air travel, we face the very real situation of a slowdown in global trade.”

Some crew members have begun refusing to work, forcing ships to stay in port. And many in the shipping industry fear that the stress and exhaustion will lead to accidents, perhaps disastrous ones.

“Owners made their contract so short for a reason,” said Joost Mes, director of Avior Marine, a maritime recruitment agency in Manila, Philippines. “The consequences are coming closer, and the margins of safety are getting less.”

Seafarers have to stay vigilant. Standing in the wrong spot on deck, or missing a step on a long, narrow ladder, could mean injury or death. A distracted watch officer could miss an approaching vessel until it is too late.

“I can see the fatigue and stress in their faces,” Santillan said in July from his ship, referring to the five men who worked with him on the deck. “I’m sure they can see it on my face.” He said they sometimes worked 23-hour days to meet their schedules.

Three of the 20 crew members on a bulk carrier that ran aground off Mauritius in late July, spilling 1,000 tons of oil into the pristine waters, were on extended contracts, according to Lloyd’s List, a maritime intelligence company. The cause of the accident has not been determined, but the seafarers’ union said it pointed to the potential consequences of having an overworked crew. Two of the ships’ officers have been charged with unsafe navigation according to the reports published in moneycontrol.com.

In a June survey by the seafarers’ union, many crew members on extended contracts said exhaustion was affecting their ability to focus. Some compared themselves to prisoners or slaves, according to the survey, and some said they had considered suicide.

Members of one crew had to shave their heads after running out of shampoo because no one could go ashore for provisions, according to the survey. Another ship’s captain had to pull the tooth of a seafarer who could not go ashore to see a dentist, a shipping company executive said.

“If someone is hurt, there is no hospital,” said Burcu Akceken, chief officer of a chemical tanker that was anchored off Dakar, Senegal, who is from Turkey.

Many stranded crew members said governments should do more to accommodate crew changes.

“Ports and countries want the cargo, but when it comes to the crew who are bringing the cargo to them, they are not helping us,” said Nilesh Mukherjee, chief officer on a tanker carrying liquid petroleum gas, who is from India.

Even in normal times, replacing a crew member involves complex logistics, said Frederick Kenney, director of legal and external affairs at the International Maritime Organization, a U.N. agency that oversees global shipping.

Leaving a ship, and getting home, requires more than just disembarking. It usually involves multiple border crossings, flights with at least one connection, and a slew of certificates, specialized visas and immigration stamps. A crew member’s replacement has to go through the same steps.

Every step in that procedure is “broken” because of the pandemic, with flights limited, border controls tightened and many consulates closed, according to Kenney. While some countries have found ways around the problem, “the rate of progress is not keeping up with the growing backlog of seafarers,” he said last week.

Some ports have exempted crew members from border restrictions, then backtracked after seafarers, arriving from their home countries to report for duty on a ship, were found to have COVID-19.